Resources

School-Based Health Centers Toolkit

We support equity for all.

Resources

School-Based Health Centers Toolkit

We support equity for all.

School-Based Health Centers and Other School Health Programs: A Toolkit for Pediatricians

School-Based Health Centers and Other School Health Programs: A Toolkit for Pediatricians

Prepared by the School Health Committee for the Georgia Chapter American Academy of Pediatrics, July 2024.

Introduction

Introduction

According to 2023 Kids Count, 17% of all children nationwide (12.2 million children) are living in poverty and are at a greater risk for a variety of negative outcomes including:

Increased rates of health problems and mortality, and

Increased risk of academic underachievement and school drop-out.

Unaddressed health needs impact a student’s ability to learn. Students with chronic health conditions are more likely to miss school due to symptoms associated with their illness or seeking treatment during the school day. Students may also miss school due to oral or behavioral health issues. School nurses, in addition to their other responsibilities, can help manage a student’s health needs during the school day. School-based health centers (SBHCs) can provide comprehensive medical care and for some students serve as a medical home.

SBHCs are recognized as an effective means of delivering physical health, behavioral health, and dental services that can significantly reduce barriers to health care for those living in poor communities. The barriers of cost, transportation, and hours of operation along with the lack of knowledge around how to manage one’s health and when to access healthcare are readily addressed through SBHCs. SBHCs not only increase access to healthcare, but also improve school attendance and academic achievement for these students.

The scope of services for these centers includes but are not limited to:

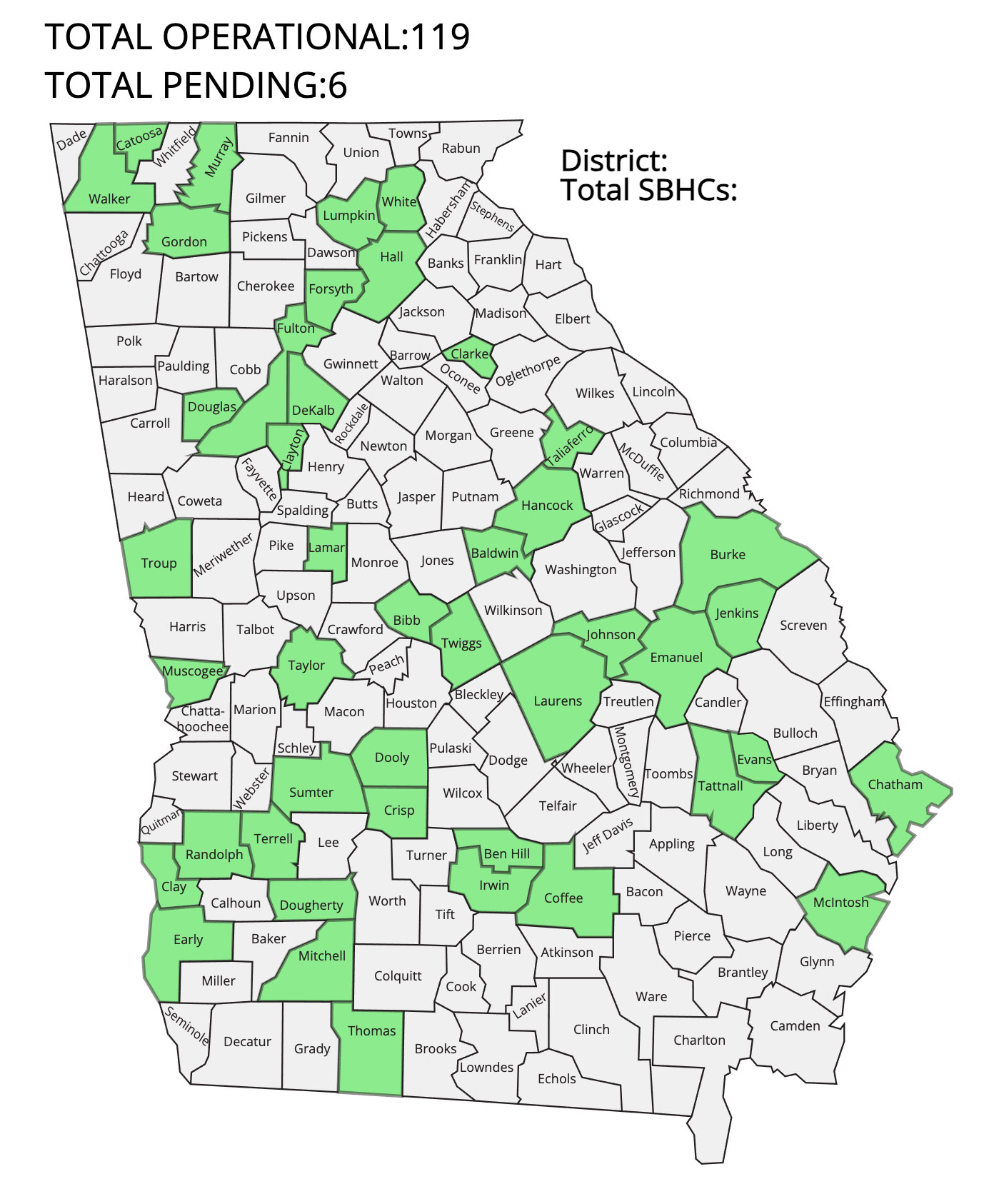

In 1994, the first comprehensive SBHC in Georgia was created and managed by Emory University School of Medicine’s Department of Pediatrics. For over 18 years, there were only 2 SBHCs in Georgia. Since 2013, SBHCs in Georgia have increased exponentially (i.e., 2 to117) under the guidance of PARTNERS for Equity in Child and Health within Emory’s Department of Pediatrics.

In 2022, Governor Brian Kemp allocated $125 million for the expansion of school-based health centers (SBHCs) throughout the state of Georgia. The purpose of this funding is to increase access to healthcare for children and adolescents living in under resourced communities and to improve academic achievement for students enrolled in Georgia’s lowest performing schools. These SBHCs will be operated by community-based medical sponsors and each medical sponsor will receive $680,000+ over a 2-year period for start-up costs (i.e., staffing, equipment, supplies). The school district will receive $300,000+ to cover renovation costs or the purchase of a modular unit to house the SBHC.

Georgia’s Department of Education is administering the program and the Georgia School-based Health Alliance (GASBHA) is providing technical support. Currently, 30 grantees are in various stages of planning and starting SBHCs throughout the state.

Pediatricians are encouraged to explore how they can collaborate with their local school districts to consider the possibility of serving as a medical sponsor for a SBHC in their respective communities.

A medical sponsor operates independently and collaboratively with the school to provide medical and mental health services for students, their siblings, and if within their capacity, the school staff. The sponsor is responsible for:

- Providing pediatric primary care services

- Hiring and Managing staff

- Outfitting the health center (i.e., medical supplies and equipment, furniture, IT equipment, etc.)

- Providing janitorial services

- Referrals to subspecialty care

- After hours coverage

For the pediatrician and other medical sponsors, the SBHC is an extension of their practice and often increases access to their existing patient panel but can also serve as a medical home for students who do not have access to a medical home. The sponsor coordinates care with other medical providers in the community, especially for those students who have a medical home.

The purpose of this toolkit is to provide guidance, instruction and technical assistance for those interested in participating in the expansion of these centers throughout the state. Visit www.gasbha.org for questions or additional information.

We hope you find this toolkit helpful. Please contact us vjohn01@emory.edu with suggestions or comments for future updates.

Scaling School-Based Health Centers

Scaling School-Based Health Centers

To effectively replicate this healthcare model, four basic elements are required:

- Recognized community needs and support

- Evidence of health and cost impact

- Sustainability, and

- Fidelity to an exemplar model

Following an exemplar model (Whitefoord Elementary School-Based Health Center founded in Atlanta, Georgia in 1994) and under the direction of PARTNERS for Equity in Child and Adolescent Health of the Department of Pediatrics at Emory University, the Georgia SBHC project was created to expand SBHCs in Georgia with 3 key phases that support the four basic elements for scaling:

The planning process occurs over a minimum of one year and can be extended into 2 years or more. From implementation to sustainability, there is usually a minimum of 3 years. For some centers, it may take longer to reach sustainability.

Implementation is dependent on funding and constructing mutual agreements between school and medical sponsor on how the SBHC should operate along with defining liabilities and determining where specific liabilities reside.

Factors impacting sustainability are patient volume (number of students in a school), patient enrollment and utilization, ability to serve siblings of students in school, ability to integrate into the culture of the school, perceived value of SBHC services by school and parents, cultural or language barriers, and financial efficiency and support of medical sponsor.

Development At a Glance

Development At a Glance

Planning

- Apply for Planning Grant

- Develop community advisory group

- Perform a needs assessment

- Visit existing SBHCs to better understand operations/scope

- Identify which schools would be best served

- Identify a potential medical provider/sponsor

- Develop a business plan

Implementation

- Engage and obtain approvals from district and school

- Plan budget

- Procure funding

- Develop SBHC Advisory Council

- Identify and renovate space

- Hire staff

- If FQHC-sponsored – obtain “change of scope” approval from HRSA

- Enroll in insurance plans

- Credential staff with insurance programs

- Market/outreach to recruit/enroll patients

Sustainability

- Develop strong partnerships between stakeholders

- Develop robust marketing/outreach plan to continue enrolling sufficient patients

- Further develop business model to maximize billing/collections

Planning Phase

Planning Phase

It is important that the community is informed about the basic tenets of SBHCs and the value they provide to the students, parents, faculty, staff, and the community at large. Planning grants are awarded to communities for the purpose of increasing knowledge and public will around the development of SBHCs. Grantees are required to create a community advisory group consisting of stakeholders in child and adolescent health and education to guide the planning process.

Responsibilities of advisory group:

- Provide guidance and direction and assists with the identification of resources and funding for the development of the SBHC.

- Educating the community on the value of SBHCS and increasing public will around the development of these centers.

Members should include but are not limited to:

- Local school system (LEA); administrators; board members; school nurse

- Health care providers such as Community Health Centers/Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs); pediatricians; academic centers; hospital systems; faith-based organizations, health departments

- Community agencies and child advocacy organizations

- Local foundations, businesses, and other potential funders

- Parents, etc.

Additional responsibilities of advisory group:

Participate in site visits of an SBHC to better understand operations and scope.

Determine scope of services and how staffed.

Identify which school(s) in the district that would be best served by a SBHC.

Perform a needs assessment to define the health and academic needs of students. The needs assessment identifies specific health problems in the community, the type of services and resources available to address those needs, gaps in service delivery and current barriers to care (physical, mental, and oral health).

Develop a business plan (a collaboration between the school system, community-at-large, and the medical provider) to determine the financial needs and resources available to support the implementation and sustainability of the SBHC.

Determine hours/days/months of operation. For example, will the SBHC be open 5 days per week or fewer; 8 hours per day or fewer; 12 months per year, or only when school is in session?

Determine the SBHC delivery model. The most common models are:

- Onsite within the school (requires repurposing of existing space with associated costs)

- Modular unit on school grounds (requires purchase of modular unit and outfitting of unit)

- Mobile unit which can serve multiple school locations

At the end of the planning year, it is expected that:

- The community will have a clearer understanding of the healthcare needs of their children and adolescents.

- A determination will be made whether a SBHC is needed.

- A clearer understanding of the costs associated with start-up and sustainability.

- The targeted school for the development of a SBHC will be identified.

- A potential medical provider/sponsor for the SBHC will be identified. For Example:

- Pediatricians or Family Physician

- Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs)

- Local hospital systems

- Academic medical systems

- Health Department

Implementation

Implementation

Implementation of a SBHC involves the following:

Creation of a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU between LEA and medical sponsor) (See Sample Memorandum of Understanding)

Establishing and monitoring enrollment, utilization, and quality metrics

For FQHC sponsoring organizations, obtaining a ‘Change of Scope’ approval from Health Resources & Services Administration (HRSA)

District and School engagement along with School Board approval

Hiring of staff

Identification and renovation of space for SBHC

Enrolling SBHC site in Medicaid, PeachCare, and private insurers

Credentialing staff with Medicaid, PeachCare, and private insurers

Student recruitment and enrollment (includes marketing and outreach)

Steps toward implementation involve budget planning and the procurement of start-up funds, creation of a Memorandum of Understanding, marketing strategies, and the creation of the SBHC Advisory Council. In considering costs for a SBHC start up, a sample budget has been developed. (See Sample SBHC Start Up Budget).

Budgets should include costs for:

1. Space Renovation

If within the existing school building:

This could be the responsibility of the local school system (LEA), the medical sponsor or a shared responsibility between the two. Occasionally, funds from other sources (foundations, governmental grants, etc.) are used for renovations.

If within a modular unit located on school grounds:

The expectation is usually a negotiation between the LEA and the medical provider on cost sharing. Other resources can be used as well.

If a mobile unit:

The expectation is that this would be funded by the medical sponsor or an outside funder.

2. Clinic Staff

Funded by and employees of the medical sponsor.

Core staff include: Physician (part-time to provide oversight), Advanced Practice Practitioner (nurse practitioner or physician assistant), Medical Assistant, Licensed Clinical Social Worker, and front office support.

- Add additional staff as funds become available (i.e., dentist, dental hygienist, optometrist, health educator, community outreach worker, etc.)

- Some members of core staff, i.e., behavioral health and dental, can be provided and funded by organizations outside of the medical sponsor.

3. Start-up Supplies and Equipment

Major medical equipment (exam beds, medical devices, etc.)

Major office equipment (copiers, scanners, computers, etc.) and furniture

Start-up medical and office supplies (See Start-up Equipment List)

4. Janitorial Services

The school janitorial services are not aligned with what is required to clean and disinfect a medical clinic (SBHC).

The SBHC should hire an entity licensed and trained to provide this service.

5. IT and Translational Services

(for some sites)

5. IT and Translational Services

(for some sites)

Marketing

Marketing is a key component to implementation as it is critical in the enrollment and utilization of the SBHC services as well as educating the public (school, parents, and community) on the value of SBHCs. Strategies include but are not limited to:

Creation and distribution of flyers, brochures, newsletters, and other forms of written communication

Inclusion of SBHC on school and school district websites

Presentations at school and community events (i.e., health fairs, school programs)

Social media (Facebook, Twitter) campaigns

Press releases

Public service announcements

Note: Marketing is a continuous and ongoing activity.

Advisory Council for the SBHC

It is recommended that an advisory council be created for the purpose of providing oversight and advocacy for the SBHC. Many members of the advisory group from the planning phase can continue in this capacity; however, it is recommended that other members from the community and school district be added to provide broader oversight and advocacy. Staff from the SBHC should be included. This will ensure quality and alignment of services with school and community needs and to provide guidance and feedback as needed. At a minimum, Council members should consist of school administrators, medical sponsor, school nurse and other school personnel (i.e., counselors), SBHC staff, parents, and community members (school board/local politicians).

NOTE:

SBHC staff do not replace school personnel, but rather complement services already provided by school nurses, counselors, and family liaison workers.

SBHCs adhere to HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) protocols to ensure confidentiality of medical information and acknowledge FERPA (Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act) protocols to ensure confidentiality of student educational information. Sharing of information is only accomplished through parental consent.

Sustainability/Conclusion

Planning Phase

From historical data, most SBHCs require at least three years of extramural funding to become sustainable. It takes that amount of time to recruit and enroll a sufficient patient base that will utilize the services for whom the SBHC can bill. Sustainability depends not only upon patient utilization but also on insurance status and patient satisfaction which is a reflection of the patients’ perception of the quality of care they receive. Finally, sustainability involves strong business practices and community collaboration.

The School-Based Health Alliance has developed a sustainability model.

Sustainability plans should include the following key components:

Develop strong partnerships between the school district, the medical sponsor, school administration, school nursing staff, parents, and the community at large.

Robust program marketing outreach and promotion to recruit a sufficient number of patients to utilize the services of the SBHC.

Establish quality benchmarks to promote healthy outcomes and patient satisfaction.

A strong business model to maximize billings and collections from Medicaid and private payers while ensuring that all patients are seen regardless of their ability to pay.

Conclusion

School-Based Health Centers are a proven model of healthcare for children and Adolescents living in under-resourced communities. They provide care in the context of all factors that impact the health and well-being of students (i.e., home, community, and school) and eliminate most barriers to healthcare (i.e., cost, transportation, hours of operation, lack of parental leave from work, etc.). Research has demonstrated that these centers not only improve access to health care, but they also improve health outcomes (i.e., asthma, mental health), increase school attendance and performance, and reduce the cost of healthcare.

School-Based Mental Health

School-Based Mental Health

Behavioral Health services are a significant component of all SBHCs. According to the CDC’s Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance Data Summary & Trends Report, in 2021, 42% of students felt persistently sad or hopeless, 22% of students seriously considered attempting suicide and 10% attempted suicide. These rates are disproportionately higher for some groups, including students of color, LGBTQ+ students, and girls.

Common conditions seen in school-age children include:

- Anxiety

- Depression

- ADHD

- Trauma, including physical and psychological abuse

- Aggression and Bullying

- Eating disorders

- Gender identity issues

- Substance use

In addition to affecting students’ overall well-being, these conditions can negatively affect school attendance and performance as well as relationships with peers and family members. They can also increase the likelihood of suspensions/expulsions as well as high-risk behaviors. Schools have increasingly become the major source of mental health care for students as the shortage of community mental health providers has worsened.

In Georgia, many have linked with mental health organizations in their community to provide mental health services to students directly in the schools. The Georgia Apex program, funded by the Georgia Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities (DBHDD), is working with schools in every county in the state to facilitate these collaborations and is an important supplement to the mental health services also offered at SBHCs.

Mental health services at SBHCs are delivered differently from most school-based mental health programs. These services are integrated into the primary care system of care which is viewed as the ‘whole child’ approach. All aspects of a child’s well-being (physical, emotional, and social) are considered in assessing and treating their mental health problems. It has been demonstrated that students who receive mental health services at SBHCs are 10 times more likely to have a mental health or substance abuse visit than a student without access to a SBHC. This integrated model increases parental buy-in and participation and reduces the stigma of receiving these services.

Pediatricians can support the delivery of mental health services in schools by:

- Serving as a referral source

- Providing relevant physical health information/background to assist mental health provider(s) in providing care through the ‘whole child’ approach.

- Prescribing medications for common mental health conditions

- Encouraging families to participate in treatment plans

- Providing in-classroom instruction to students on behavioral health topics

- Participating in IEP staffing for children requiring additional specialized services

FAQs & Resources

FAQs & Resources

FAQs

FAQs

Resources

Resources

Prepared by

The School Health Committee Georgia Chapter

American Academy of Pediatrics

Special thanks to Summer Gilmer-Hughes, Georgia AAP